Real Bus Grope

The Complex Reality of Non-Consensual Touching on Public Transit

Public transit systems are the lifeblood of urban mobility, connecting millions daily. Yet, beneath the surface of this essential service lies a pervasive issue: non-consensual touching, often colloquially—and misleadingly—referred to as “groping.” This phenomenon transcends cultural boundaries, impacting commuters across Tokyo, New York, Delhi, and beyond. To address it requires dismantling myths, understanding systemic failures, and implementing multifaceted solutions.

Defining the Problem: Beyond Sensationalism

The term “grope” trivializes a spectrum of violations, from brushing against someone due to overcrowding to deliberate sexual assault. In Japan, where the issue gained global attention, it’s termed chikan—a word that obscures the severity of actions ranging from unwanted touching to forced penetration. In India, the 2012 Delhi gang rape sparked public outrage, yet everyday harassment on buses persists. The U.S. lacks comprehensive data, but surveys reveal 1 in 4 women experience unwanted contact on transit.

Root Causes: A Convergence of Factors

Overcrowding: In Tokyo, rush-hour trains operate at 200% capacity, creating environments where accidental contact becomes indistinguishable from intentional assault.

Social Conditioning: In many cultures, public harassment is normalized. A 2017 UN study found 90% of Indian women avoided reporting transit harassment due to stigma or fear of retaliation.

Impunity: Legal loopholes and low conviction rates embolden offenders. In Japan, only 10% of chikan cases reported in 2020 led to arrests.

The Human Toll: Invisible Scars

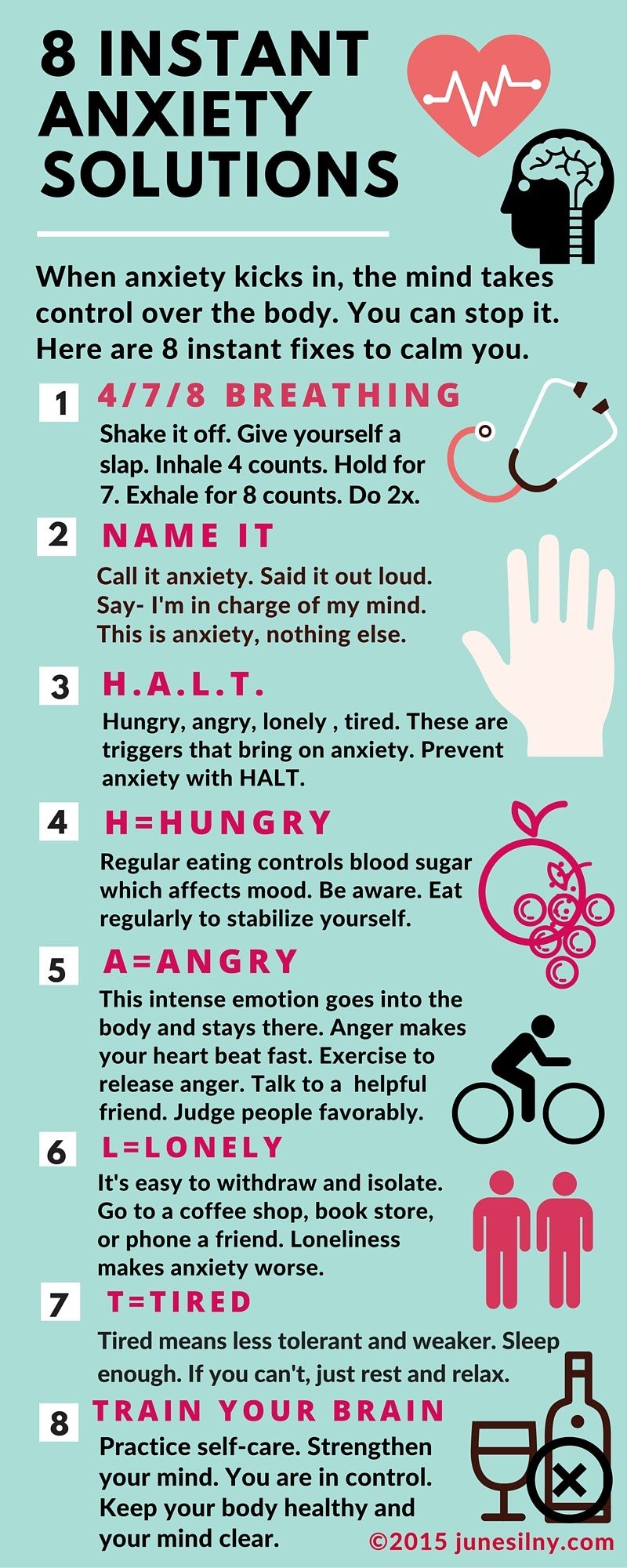

Survivors describe a spectrum of trauma. Maria, a 28-year-old commuter in Mexico City, recalls: “I froze. The bus was packed, and no one intervened. I felt invisible.” Psychologists link such experiences to anxiety, PTSD, and avoidance of public spaces. A 2021 study in the Journal of Urban Health found 43% of affected women altered their routes or avoided transit altogether.

Global Responses: Patchwork Progress

| Country | Initiatives | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Japan | Women-only train cars, anti-chikan apps | Mixed; critics argue segregation avoids root issues |

| Brazil | Mandatory reporting training for drivers | Early success, but underfunded |

| Philippines | Dedicated “pink buses” for women | Limited reach in rural areas |

Technological Interventions: Promise and Pitfalls

CCTV cameras and emergency buttons are standard in Seoul’s metro, correlating with a 30% drop in reported incidents since 2015. However, technology alone is insufficient. In Cairo, where harassment is endemic, cameras often malfunction, and complaints are dismissed.

Cultural Shifts: The Role of Education

Belgium’s “Hands Off” campaign uses graphic novels to teach consent in schools, while Sweden integrates bystander training into corporate workshops. Such programs challenge norms but require sustained funding and political will.

Legal Reforms: Closing the Accountability Gap

France’s 2018 law fines catcalling and groping up to €750, yet enforcement remains inconsistent. In contrast, Singapore’s mandatory jail time for public molestation sends a clear deterrent, though critics highlight underreporting.

The Way Forward: A Holistic Framework

- Infrastructure Redesign: Wider aisles, transparent partitions, and real-time capacity monitoring.

- Community Engagement: Train bystanders to intervene safely, as modeled by New York’s RightRides program.

- Survivor-Centric Policies: Anonymous reporting apps and trauma-informed police training.

Why don’t more victims report incidents?

+Fear of disbelief, retaliation, or re-traumatization during legal processes discourages reporting. In Delhi, only 1% of transit harassment cases are filed.

Do women-only cars solve the problem?

+They offer temporary safety but reinforce gender segregation. Critics argue for system-wide reforms instead.

How can bystanders help safely?

+Create distractions (e.g., asking for directions), alert authorities, or use apps like SafeCity to document incidents.

Conclusion: Reimagining Transit Equity

Non-consensual touching on buses and trains is not an inevitable urban tax but a solvable crisis. It demands collaboration between governments, technologists, and communities. As cities expand, their transit systems must evolve—not just in efficiency, but in humanity. The right to move freely, without fear, is not a privilege; it is a fundamental right.

*"Safety is not the absence of danger, but the presence of systems that protect dignity."* —Urban planner Jane Jacobs, 1961

This issue, often whispered but rarely confronted, requires us to rewrite the rules of public space. The journey begins with acknowledgment—and ends only when every commuter steps off the bus with their autonomy intact.